"It's crucial that we take rabbits' needs for a companion seriously".

Researchers compare the welfare of single versus paired rabbits

Housing rabbits in pairs reduces stress-related behaviour and helps them keep warm in winter, according to new research.

Findings published in the journal Animal Welfare suggest that social housing prevents rabbits from biting at the bars of their hutch, helps them to keep warm, and may even relieve stress.

The study by researchers at the Royal Veterinary College (RVC) also found that body temperature was significantly lower in single rabbits than pairs.

“It was really sad to discover that lone rabbits were so much colder than the paired ones, and that more than half of them were seen biting at the bars of their enclosures," commented Dr Charlotte Burn, associate professor in animal welfare and behavioural science at the RVC.

“It’s crucial that we take rabbits’ needs for a companion seriously. There is a culture of getting ‘a rabbit’ and this needs to change, meaning that pet shops, vets and animal welfare charities should advise owners on housing rabbits with a compatible partner. Part of the enjoyment of having rabbits is surely to see them playing and resting together, especially when we give them suitably large housing.”

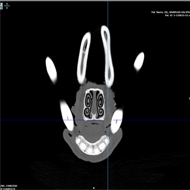

In the study, researchers compared the welfare of 45 rabbits, comprising 15 housed alone and 15 housed in pairs. The research was conducted during wintertime at the Rabbit Residence Rescue, located on the Hertfordshire/Cambridge borders. The single rabbits were mostly in smaller enclosures than the pairs, and were awaiting a suitable partner for pairing.

Rabbits are naturally social creatures, but they are also territorial. It is for this reason that researchers predicted singletons would exhibit more stress-related behaviour, and reduced body temperature, but that pairs may be aggressive towards each other.

The team observed bar-biting in eight of the fifteen single rabbits compared with none of the 30 paired rabbits – a behaviour that has been previously linked to frustration and attempts to escape. For around one-third of the time, pairs interacted socially; huddling together, grooming or nuzzling each other. Interestingly, the researchers did not observe any aggression between the pairs.

The team also observed that, on colder days, there was on average at least 0.5 degrees Celcius difference between single rabbits and the paired rabbits. They also noted that rabbits adopted compact postures more often, and relaxed postures less frequently, indicating that they were actively attempting to keep warm.

Commenting on the findings, Lea Facey, manager of The Rabbit Residence Rescue Charity, said: “It’s so important for the advancement of rabbit welfare that these issues are highlighted."

The compatibility of individual rabbits is an important factor to consider, and it can be difficult to pair rabbits without them becoming stressed or aggressive, or having unwanted litters, she said.