The study found that spaying can increase the risk of more aggressive cancers.

Higher serum oestrogen levels linked to improved survival times

US researchers have shed new light on the complex role of oestrogen in the development of canine mammary tumours.

The study, published in PLOS ONE, found that while spaying at a young age can reduce a dog’s risk of developing mammary cancer, it can increase the risk of more aggressive cancers.

Furthermore, the study found that in spayed animals with mammary tumours, higher serum oestrogen levels were protective, associated with longer times to metastasis and improved survival times.

Senior author and veterinary oncologist Karin U Sorenmo from the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Veterinary Medicine (Penn Vet), said: “Dogs that remain intact and have their ovaries develop many more mammary tumors than dogs that were spayed, so removing that source of estrogen does have a protective effect.

“Estrogen does seem to drive mammary cancer development. But what it does for progression to metastasis—that I think is more complicated.”

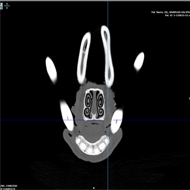

In the study, researchers assessed 159 dogs with mammary cancer, 130 of which were spayed as part of the study and 29 that remain intact. Besides surgically removing the dogs’ measurable tumours, the team collected information on serum oestrogen levels, tumour types, disease grade and stage, time to metastasis, and survival time.

They found that, despite oestrogen’s link with an increased risk of developing mammary tumours, higher serum oestrogen levels appeared to help dogs avoid some of the riskiest aspects of their disease.

Interestingly, when dogs were spayed at the same time as having their tumours removed, those with oestrogen-receptor positive tumours that had higher serum oestrogen took longer to develop metastatic disease and survived longer than dogs with lower oestrogen levels - confirming that such tumours depend on oestrogen for progression.

The researchers also found that the protective role of oestrogen was also pronounced in dogs with oestrogen-receptor negative mammary tumours. In these higher-risk cancers, high serum oestrogen was associated with delayed or absent metastasis.

Furthermore, the study showed that dogs with low oestrogen are at a far higher risk for developing other non-mammary aggressive fatal tumours after mammary tumour surgery.

Sorenmo and her colleagues have been studying mammary tumours in dogs as a way to improve care and treatment for pets, but to also reveal insights into human breast cancer.

Their research used data from the Penn Vet Shelter Canine Mammary Tumour Program, through which shelter dogs with mammary tumours receive treatment, are studied by researchers like Sorenmo, and found foster or permanent homes.

Image (C) Penn State University.