The body’s response to the first infection produces more of the type of red blood cell that the second parasite requires.

One type of parasite helps the other to survive

Scientists at the University of Edinburgh have discovered why infections with two types of malaria parasite lead to greater health risks.

A study, published in the journal Ecology Letters, describes how researchers found that one type of parasite helps the other to survive.

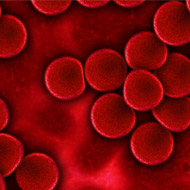

In humans, a parasite known as P.falciparum infects red blood cells of all ages, while another - P.vivax - only attacks young red blood cells.

But a new study in mice with equivalent malaria parasites shows that the body’s response to the first infection produces more of the type of red blood cell that the second parasite requires.

Millions of red blood cells are destroyed in response to the first reaction, and the body responds by replenishing these cells, the scientists explain. These fresh cells quickly become infected by the second type of parasite, making the infection worse.

Researchers say the finding could explain why infections from both P.falciparum and P.vivax in humans have worse outcomes for patients than single infections.

"Immune responses are assumed to determine the outcome of interactions between parasite species but our study clearly shows that resources can be more important,” said Professor Sarah Reece of the University of Edinburgh’s School of Biological Sciences.

“Our findings also challenge ideas that one species will outcompete the other, which explains why infections involving two parasite species can pose a greater health risk to patients,” she adds.

Zoetis has launched a new survey to identify management techniques for Equine Herpes Virus (EHV).

Zoetis has launched a new survey to identify management techniques for Equine Herpes Virus (EHV).